Open by Design: A Series on Clarity, Coherence, and the Craft of Modern Architecture

The Quiet Rebirth of Architecture

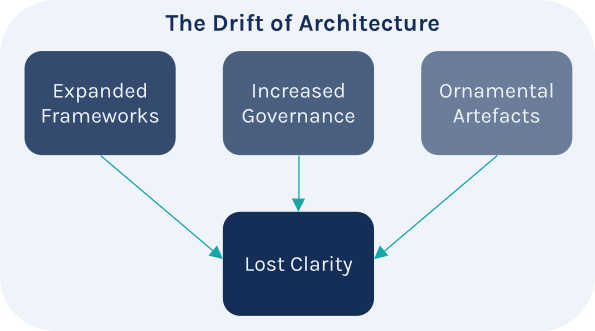

For more than a decade, it has felt as though Enterprise Architecture has quietly drifted away from the purpose that originally gave it power. What began as a discipline intended to create understanding and coherence became increasingly associated with frameworks, role inflation, assurance gates, and artefacts that grew in volume but not in value. Many organisations built towering repositories of models and diagrams, only to discover that those assets rarely influenced the decisions that mattered.

This decline wasn’t caused by a lack of talent or intent. It came from the gradual elevation of practice over purpose. Teams produced capability maps disconnected from investment, process models disconnected from reality, and architectural standards disconnected from delivery. In the absence of clarity, organisations turned to certification, terminology, and governance rituals that created a comforting sense of order but little meaningful insight.

As a result, strategy drifted. Programmes moved without direction. Proof-of-concepts stretched into years. Data fragmented. Integrations multiplied. Automation became a patchwork of reactions instead of a design. And IT—despite being more essential than ever—was often treated as a cost-centre rather than a source of capability.

Yet quietly, beneath this noise, a shift has begun. As cloud ecosystems have multiplied, as systems have become more distributed, as data has become both an asset and a liability, and as integration has emerged as the new centre of gravity for every business process, organisations have rediscovered a simple truth:

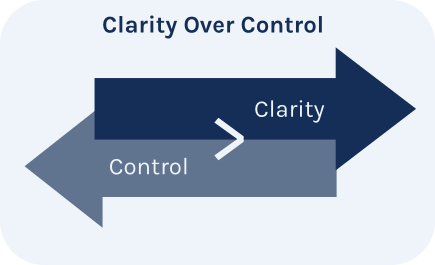

They do not need more control. They need more clarity.

And with that clarity, a very different kind of architectural practice is emerging: the pragmatic architect.

How Architecture Drifted from Its Purpose

Enterprise Architecture was originally meant to serve as the connective tissue of the organisation: a shared language that translated strategy into design, design into systems, and systems into behaviour. In that world, models existed not to impress but to inform — a way to make complex organisations understandable enough that coherent decisions could be made.

But in many organisations, something subtle began to happen. Architecture shifted from a craft to a compliance function. Instead of enabling teams to reason about change, it became a mechanism for documenting what already existed. Instead of guiding investment, it became a formality attached to procurement. Instead of designing flows through the organisation, it captured snapshots that aged the moment they were created.

This drift created an illusion of structure without the substance of clarity. Leaders saw diagrams but not decisions. Delivery teams saw governance but not guidance. Architecture became something done around the organisation rather than within it. The result was a widening gap — a system that looked mapped, but wasn’t truly understood.

When Complexity Outpaced the Models

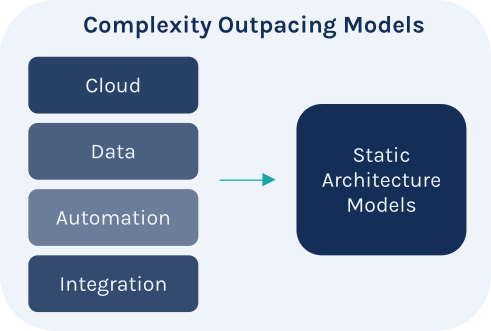

While architecture was becoming more procedural, the systems it was meant to describe evolved faster than the methods used to document them. Cloud expanded choice to the point of fragmentation. Integration became the lifeblood of every process. Data sprawled across SaaS tools, spreadsheets, and edge systems. Automation shifted from convenience to necessity. Controls became too complex to bolt on afterward.

In this world, static architectural artefacts stopped being helpful. Multi-year capability maps failed to evolve with the business. Linear process descriptions couldn’t reflect real-time systems. Integration diagrams captured only a moment in time. Data definitions fragmented across platforms. And governance frameworks slowed down teams that needed to move faster than ever.

This is where the old architecture broke: the gap between how fast systems change and how slowly models are maintained. And this is exactly where the modern discipline begins to rebuild.

The Emergence of the Pragmatic Architect

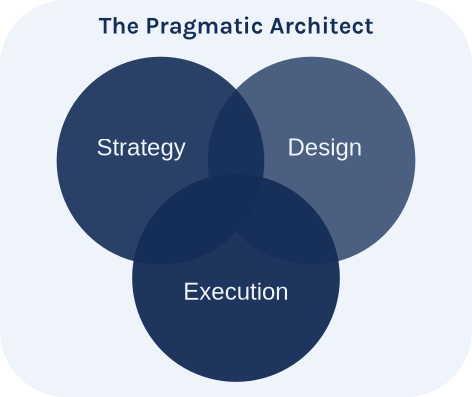

The pragmatic architect steps into the space between strategy and delivery—not to control it, but to make it coherent. Their work is not defined by the models they produce, but by the decisions those models enable. They recognise that clarity is not the result of documentation; it is the consequence of understanding. And so they design with intent, not excess.

Where traditional architecture sought completeness, pragmatic architecture seeks coherence. Instead of creating diagrams for every scenario, pragmatic architects create the views that matter — the ones that illuminate change, expose risk, and make the path forward visible.

This is why ArchiMate, when used properly, becomes central to their practice. Not as a notation or a framework, but as a thinking engine — a way to connect capability, process, data, application, integration, automation, and control into a single, traceable story. What once looked like a modelling language becomes, in their hands, a decision intelligence system.

This shift is profound: diagrams stop being pictures and start being instruments of reasoning. It’s here that pragmatic architects naturally converge on Enterprise Fabric — not because it is fashionable, but because it provides a structure that reflects how the organisation truly works. Where many frameworks prescribe ceremony, the Fabric describes reality.

Moving Beyond the Illusion of Control

For years, organisations tried to respond to complexity by adding more control. More standards. More checkpoints. More reviews. More layers. The implicit belief was simple: if we cannot understand the system, we must govern it harder.

But control without clarity does not reduce risk — it hides it. Pragmatic architects invert the equation. By revealing the structural patterns of the enterprise — its capabilities, its flows, its data, its dependencies — they make control something that emerges from design, not something imposed through process.

In this world, data quality is not enforced; it is designed. Integrations are not accidental; they are mapped. Automation is not improvised; it is aligned. Controls are not bolted on; they are embedded. The organisation becomes governable not because it is restricted, but because it is understood.

This is the moment where organisations stop trying to tighten their grip and begin to illuminate what they hold.

Open by Design: The Foundation of Modern Architecture

If pragmatic architecture is the practice, Open by Design is the philosophy behind it. To be open by design is to make the organisation observable—to design models, processes, data definitions, integration flows, and controls in a way that allows teams to see how things work, not just how they’re documented.

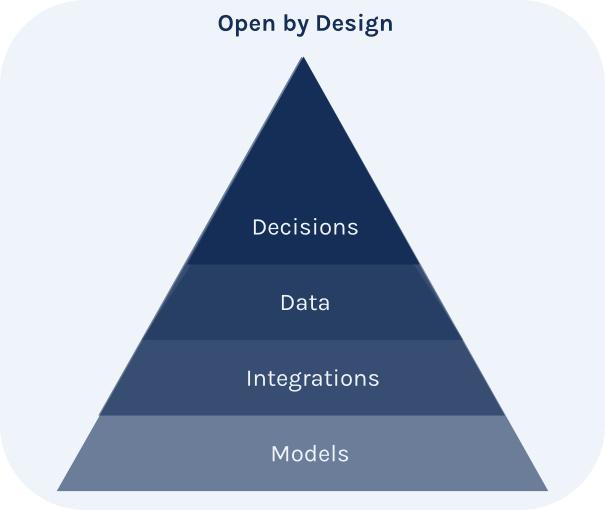

This is where Enterprise Fabric becomes essential. It provides the seven-layer structure that turns openness into a practical reality: capabilities, processes, data domains, applications, integrations, automation, and controls. When an organisation sees itself through this structure, decisions become clearer, trade-offs become explicit, and change becomes less risky.

This is why the Fabric forms the backbone of the technical reference model. It gives a language to the complexity that modern organisations cannot avoid. Open by Design is not about transparency for its own sake. It is about enabling coherence through shared understanding.

Connecting the Practice: From Insight to Deep Dive

This Insight is the beginning of a series that explores architecture not as governance, but as craft. The pragmatic architect is the guide through this journey, and the Enterprise Fabric is the map they carry.

If you want to explore how this philosophy becomes practical, over the coming weeks/months/years I’ll be adding relevant Deep Dive content.

Conclusion — The Quiet Future of Architecture

The future of architecture does not belong to those who collect diagrams or enforce process. It belongs to those who make complexity understandable. The pragmatic architect is not a new role or a rebellion against tradition. They are simply the practitioner who remembers what the discipline was always meant to be: a designer of clarity, a steward of coherence, a translator between intent and implementation, and a builder of organisations that understand themselves well enough to evolve with purpose.

This series is about that return — to architecture as thinking, as design, and as clarity. A future where organisations finally become Open by Design.